|

|

|

|

|

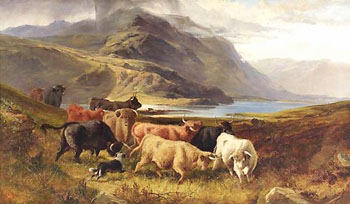

The Highland Cattle Drovers |

|

The drovers of the Scottish Highlands are among those people in history who did not individually rise to fame but collectively played an important part in their day. The Highlands, like other northern mountain areas, have hard long winters. The soils are not very fertile and often poorly drained. They are suited to rearing livestock like cattle and largely unsuited to crop growing. Historically, cattle were vital to the survival of the highlanders who lived under their clan chiefs as communities ? and latterly as tenants, growing oats, kale, and with grazing rights on commonly held land in the hills. It was in the interest of the chiefs to have as many tenants as possible, as each was a potential fighter who contributed to the strength of the clan, and each tenant |

|

|

could graze his cattle on the common land. This system encouraged over production of cattle, and in addition the long winters and infertile soils meant a shortage of stored feed to sustain cattle over the winter. The people were hardy but poor and their cattle all they could sell for money. What should be done with the surplus cattle? As in other parts of the world with this situation, the solution was to drive them long distances, on foot, south and east to where the denser human populations lay who would buy and consume the cattle. This was the source of the droving trade in cattle in Scotland and the men who drove the cattle were called "the drovers." As early as 1359 there is a record of two Scottish drovers being given letters of safe passage through England with cattle, horses and other merchandise and yet for centuries the trade did not flourish. The main reason was war. The wars of independence and later struggles between Scotland and England lasted centuries. Trade with England was seen as giving aid to the enemy and actively prevented. However, in 1603, James the Sixth, ascended the throne of England as James the First of England, uniting Scotland and England. By 1607, free trade had been agreed between the two countries, though customs duties were retained on hides and cattle. The union had another important effect that helped the droving trade. It aided the active discouragement of "rieving", that is cattle rustling, which had been widely pursued over much of Scotland including the Highlands, almost as if it was a normal branch of agriculture and would be a threat to any cattle on the move. |

|

The cattle themselves were

the precursors of today’s Highland cattle. They were much smaller than most

breeds today, probably not weighing much more than 5 cwt. (254 Kg).

Descendents of the old Celtic oxen, they were and still are the hardiest of

breeds and easy to handle. Until red/brown variants were exported from Glen

Lyon in the mid 19th century, they were black. The gene for the red/brown

colour proved to be dominant and this is now the colour of most of the breed

in various shades. |

|

cattle would have passed along the route where the military bridges now lie. How was this huge trade carried out? "The Highland cattle have a close ancestry in common with the Welsh Black, the Dexter, the Kerry, the Galloway, the Camargue cattle of France and Spanish fighting cattle. The breed also has a near relationship to the British White Park cattle, such as those at Chillingham, which were feral or free ranging herds that were enclosed for hunting in large walled parks in the 12th and 13th centuries. Many authorities have presumed that these breeds have a closer genetic relationship to wild ancestors than other domestic cattle. As the Auroch or Urus the wild Eurasian Ox is extinct this is hard to verify (the last cow is said to have died in Poland in 1627). What is indisputable is that the extensive systems of husbandry, applied |

|

to these breeds for centuries if not millennia will have had an effect. Most have been or are still kept in systems with range grazing. At times there has been little selection in breeding. Or there has been selection for non food industry qualities, such as aggression. All this will have given them an important genetic diversity in comparison to breeds intensively bred for the meat or dairy industry, in particular they have the characteristics of a biological soundness that in other breeds have been sacrificed to the requirements of agribusiness. This is their value to the future and it is to be hoped it is not to be now thrown away to meet the fashions of the show ring." |

|

|

The drovers were local men. In May, they would start to visit farms, bargaining for cattle often only one or two at a time, since many of the highland farming tenants were very poor. Gradually, they would have a herd they could gather as summer advanced and drive south. The herds would be at least 100 strong, often larger and up to 2,000 strong. Ahead of them lay a long and dangerous journey. Rivers in flood might have to be crossed; journeys must be made over trackless mountains, sometimes in thick mist where a drover might easily loose his way; or well armed "rievers" might try to steal cattle. A Drover's Day A drover's day was a long one. At about 8.00 am they would rise and make a simple breakfast of oats, either boiled to make porridge or cold and uncooked mixed with a little water. The whole might be washed down with whisky. Oats, whisky, and perhaps some onions were their basic diet. Occasionally, they might draw blood from some cattle and mix it with oatmeal to make "black pudding." The herd would move off on a broad front of several strings of cattle, moving perhaps 16-20 km or less a day. It is misleading in fact to speak of a drove "road." The cattle had to be managed skillfully to avoid wearing them down or damaging their hooves, and the drover had to know where he could obtain enough grazing along the way. At days end, the cattle might stop near a rough inn where some shelter could be obtained, or perhaps the drovers had to sleep out on the open hill in all weathers with only their tartan, woven cloth, called their plaid, to protect them. At night someone always had to guard the herd to prevent cattle straying or rievers stealing them. It was a hard and, at times, dangerous life, but the Highlanders, with their warlike, rieving past, and hardy upbringing were well suited to it. The rievers of one century in fact transformed into the legitimate drovers of another. The practice common in many mountain areas of moving livestock and people to higher areas during the summer to take advantage of high pastures, a form of what is called transhumance, was widespread in the Highlands. This practice too, developed some of the skills needed in successful droving. |

|

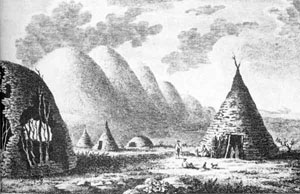

"Ascend a steep hill, and find ourselves on an Arrie, or tract of mountain which the families of one or two hamlets retire to with their flocks for pasture in summer. Here we refreshed ourselves with some goats' whey, at a Sheelin or Bothay, a cottage made of turf, the dairy-house, where the Highland shepherds, or graziers, live with their herds and flocks, and during the fine season make butter and cheese. Their whole furniture consists of a few horn spoons, their milking utensils, a couch formed of sods to lie on, and a rug to cover them. Their food oat-cakes, butter or cheese, and often the coagulated blood of their cattle spread on their bannocks. Their drink milk, whey, and sometimes, by way of indulgence, whisky...." from Pennant's Tour of 1769" |

|

The drovers might strike the people of the lowlands they entered as strange and perhaps threatening. "Great stalwart hirsute men, shaggy and uncultured and wild, who look like bears as they lounge heavily along." as one person described them at the time. But they were greatly skilled. Listing the necessary attributes of a drover, A.R.B. Haldane, who made a special study of the drove, lists the attributes they had to have as:

In addition to that, they were also often skilled on the bagpipes or learned in other aspects of their Gaelic culture. As people they should never be underestimated. The drovers would arrive finally with their cattle in specific Scottish towns like Falkirk or Crieff where they would sell on their cattle to others who moved them to places like the grazing areas of Northumberland or the Yorkshire Dales, both in northern England. There they would be grazed and fattened after their long journey before being driven further south to the London markets. For nearly two hundred years, through the second half of the seventeenth century, throughout the eighteenth century, and into the early nineteenth century, droving flourished aided by a growing human population and hence demand and other factors. Between 1727 and 1815, for example, there was a long series of wars with Spain, Austria, America, France and, finally, the Napoleonic wars. This meant a large navy had to be maintained. Salted beef was a major foodstuff for the navy, which was thus a major market. In 1794 for example, the London meat market of Smithfield recorded 108,000 cattle arriving for slaughter and at least 80% of these came from Scotland. But times were changing and droving would go into decline. The Passing of the Drovers The peace, after the battle of Waterloo in 1815 finished the Napoleonic wars, meant the shrinking navy needed less beef but other changes were even more important. The first half of the nineteenth century saw a revolution in agriculture. Enclosed systems of fields replaced open common grazing and large, fatter cattle were bred and raised ready for market. More importantly, by the 1830s, faster steamships were being built and farmers in the lowlands and elsewhere started to ship cattle directly to the southern markets instead of by the long arduous overland droves. Then, once railways were established by the 1880, this provided an even swifter and more reliable means of transporting cattle and other agricultural products to market. The trade died steadily. Droving days were over and a watcher at the bridge would have seen a different kind of passer by. |

|

Acknowledgements: By John A Duncan of Sketraw FSA Scot. adapted from an article on the "An 18th century military road in the Scottish Highlands." The Drove Roads of Scotland A R B

Haldane, Pub David and Charles, 1952 |

|